Multi-Layered MPI parallelisation for the R-matrix with time-dependence code

ARCHER2-eCSE01-11

PI: Dr Andrew Brown (Queen’s University Belfast)

Co-I(s): Prof Hugo van der Hart (Queen's University Belfast)

Technical staff: Dr Martin M Plummer (STFC)

Subject Area:

In order to ‘view’ electrons in an atom, we need to be able to capture their motion on a time-scale comparable to the interactions themselves. This is akin to taking a photograph – the faster an object is moving, the shorter the exposure time required to capture it. In atomic, molecular and optical physics we effectively use ultrashort ‘camera’ flashes (laser pulses) to image electrons in motion. While this field of attosecond physics (1 attosecond = 1 billionth of a billionth of a second) is well established, the theoretical description and computational models of the underlying mechanisms are relatively underdeveloped.

Developments in laser technology have now made it possible to observe the motion of electrons in real time and control this motion with high precision [1–5]. Attosecond physics is a natural successor to femtochemistry [6], and several of its overarching aims remain in chemical and even biological systems. Processes as fundamental as vision and photosynthesis are driven by light-mediated charge transfer in large molecules [7], while photovoltaic cells harness photoabsorption in semiconductors [8]. A key, long-term goal of ultrafast physics must be to understand these processes in more than qualitative terms. To reach that goal we must first properly understand light-matter interaction at the atomic level.

The rapid advance of laser technology has facilitated myriad new measurement techniques able to resolve time-dependent electronic dynamics in complex systems. Our community is investigating these phenomena using the world-leading R-matrix with time-dependence code (RMT) [9]. RMT solves the time-dependent Schrödinger equation for general, multielectron atoms, ions and molecules interacting with laser light. As such it can be used to model ionization (single-photon, multiphoton and strong-field), recollision (high-harmonic generation, strong-field rescattering, [10]) and, more generally, absorption or scattering processes with a full account of the multielectron correlation effects in a time-dependent manner. Calculations can be performed for targets interacting with ultrashort, intense laser pulses of arbitrary polarization. Calculations for atoms can optionally include the Breit-Pauli correction terms for the description of relativistic (in particular, spin-orbit) effects [11].

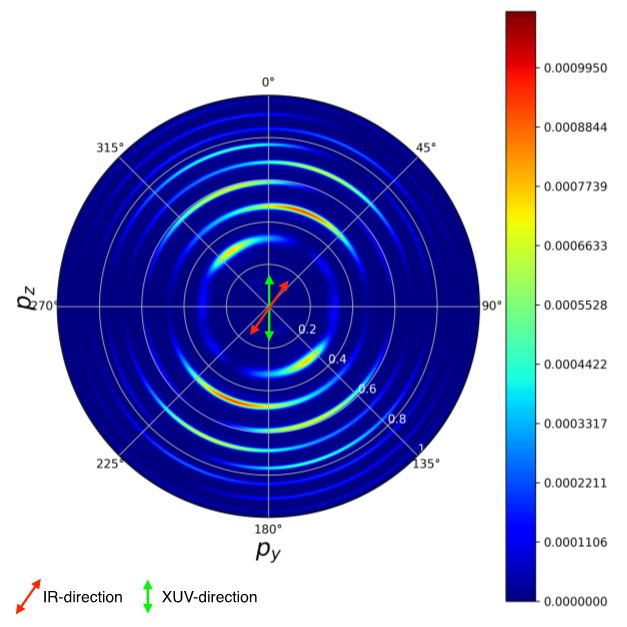

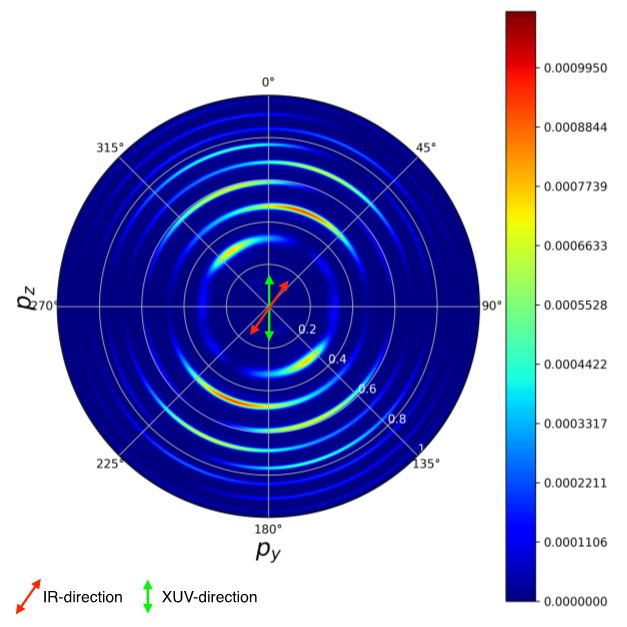

High-energy and ultrashort sources can drive multiple-ionisation phenomena which are not yet described well by theory. RMT is currently being extended to investigate double-ionisation phenomena in general multielectron atoms. Other recent successful investigations using RMT include collaborations with experimental groups on skew-polarization RABBITT (reconstruction of attosecond beating by interference of two-photon transitions) [12] and attosecond transient absorption spectroscopy [13]. The former allows the resolution of individual pathways in quantum interference and the latter demonstrates real-time analysis of resonant processes during strong-field ionization.

Figure 1: Photoelectron spectrum following multiphoton ionization of Helium in a skewed IR/XUV RABBITT scheme. The IR (infra-red) laser pulse is polarized in a plane oriented at the 'magic' angle of 54.7° relative to the XUV (Extreme Ultraviolet) attosecond pulse train. At this angle, the two-photon ionization pathway is suppressed, and we observe four-photon processes, leading to unusual behaviour in the phase and amplitude of the so-called ‘sideband oscillations’. A full simulation of this process requires multiple ‘snapshots’ wherein the time-delay between the XUV and IR pulses is varied over some range. For brevity, only a single snapshot is shown.

The functionality extensions have increased the size of RMT calculations by orders of magnitude, and the already complex parallel structure of the code must be enhanced to deliver current scientific goals efficiently and pave the way for more ambitious projects. This eCSE project has introduced new parallelism at the basic level to RMT to enable new leading-edge calculations by our community, and to greatly improve the efficiency of ongoing current application calculations.

The R-matrix approach divides the problem into two distinct regions: an inner region (IR), in which all electrons are close to the nuclear centre of mass, and an outer region (OR), in which one electron (two in the double-ionisation project) has moved away from the nucleus or nuclei. There are completely separate parallelization schemes to suit the different mathematical descriptions of the dynamics in the regions. In the small IR a basis set expansion is used to give an accurate description of multielectron correlation, while in the large OR the one-electron wavefunction is described on a finite-difference grid. We have introduced a new layer of MPI parallelization in each region. These (i) greatly increase the flexibility of allocation of IR MPI tasks to all-electron interacting blocks of distinguishable (angular and spin) symmetries, and (ii) allow full MPI parallelization of OR wavefunction component ‘channels’ within a radial grid sector (the grid is already MPI-parallelized). We have also developed a systematic approach for allocation of MPI tasks between the two regions for optimal performance.

- [1] Nat. Phys., 3, 381 (2007)

- [2] Phys. Today, 64, 36 (2011)

- [3] Chem. Phys., 414, 1 (2013)

- [4] Nat. Photon., 8, 195 (2014)

- [5] Nat. Photon., 8, 205 (2014)

- [6] J. Phys. Chem. A, 104, 5660 (2000)

- [7] Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 25, 971 (1986)

- [8] J. Photochem. Photobio. C: Photochem. Rev., 4, 145 (2003)

- [9] Opt. Lett., 41, 709 (2016)

- [10] see, for example, Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 093201 (2016)

- [11] Comput. Phys.Commun., 250, 107062 (2020)

- [12] Nat. Comm., 13, 1, (2022)

- [13] J. Phys. B. 55, 245601 (2022)

Information about the code

The RMT repository is hosted on GitLab, with an expanding number of continuous integration features, a test suite and strict rules for descriptions of code updates. The code is supported by detailed documentation using doxygen, The RMT code and its applications are described in detail by Brown et al (Computer Physics Communications 250 (2020) 107062).